For PR pros, summer is a time to recharge, take off a few days, eat ice cream (see page 6), read (p. 10), perhaps watch The Olympics (p. 3 and 16) before returning to work and crafting budgets for the coming year.

Owing to the state of the world in 2021, perhaps budgets will include more pro bono slots than previously.

When we heard about the story of a young woman you’ll read below, PRNEWS decided to delve into how companies and PR firms decide on pro bono projects.

For example, is there a formal decision process? Do they:

- Budget a percentage of time every quarter to pro bono?

- Survey employees to see what activities and causes are on staffers’ minds?

- Have committees that oversee pro bono work?

Or is it informal? ‘One of our employees has a relative with a medical condition, so we’ve worked pro bono for one of the groups in that space.’ Or ‘ABC Charity, whose office is in our building, approached our senior partner about helping with fundraising. So, that’s our pro bono work.’

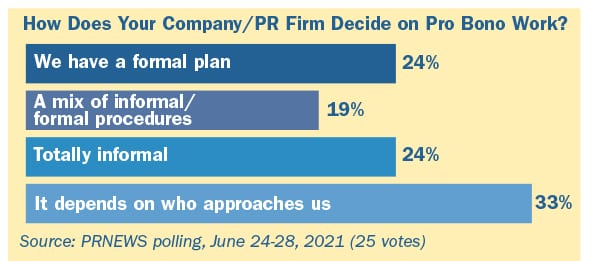

An unscientific snap poll we took recently seemed to indicate it’s a mix of formal and informal processes (see chart).

In interviews, we found pro bono has several meanings. Strictly, it’s free work. In PR, it also encompasses volunteering at nonprofits. At some shops it includes at-cost or highly discounted work. Some brands consider pro bono tantamount to what many call corporate social responsibility.

Now to the story we mentioned earlier. It’s October, 2002. The setting is a train station in Maoming, China, some 1,700 miles south of Beijing.

A shoebox is left inside the station. Although there’s no way to be certain, the box likely sat untouched for a period of time. A police officer found the box and opened it.

Inside was a newborn girl, 3 pounds, umbilical cord still attached.

The baby seemed safe, though ‘safe’ is relative. She was little more than a number in a country where overpopulation has plagued authorities for centuries, though there’s evidence the western perception of China’s disdain for daughters is an oversimplification. In any case, spending one’s earliest days in a shoebox is not the best way to begin life.

First 10 Months in an Orphanage

It’s little surprise that adopted children are more prone to mental health issues as youngsters than those living with their biological parents. It’s likely these 10 months influenced the child’s formative years. A newborn left inside a box at a Chinese train station has no choice.

Around the time the box was found, the Lincolns, a couple living in Easton, PA, had a decision to make. Either the couple would try to conceive a third child–they wanted a girl to complement their two biological sons–or go to China hoping to adopt.

Roughly one year after the box was opened, the girl inside it had a new family. Ayden Lincoln came ‘home,’ to Easton.

“I struggled right away,” she told us recently. “I wouldn’t stop talking in class [and]…I was fidgety…a bumblebee…I acted out and my teachers responded with harsh discipline. And I’d act out even more. I would cry and have panic attacks…words can’t describe the feeling. I was a 7-year-old child who didn’t know what I was doing wrong. The only thing I knew was to not stop talking in class or running around the classroom…I felt isolated.”

Some Hope

In third grade there was hope. Ayden met “an amazing teacher, Kristel Carter-Sell, who literally changed my life…she really cared for me and talked to me, instead of sending me to the principal’s office. She held me like a baby and let me cry on her when I was having a meltdown.”

Skip to high school and Ayden, who graduated two months ago and is set to attend Northampton Community College in the fall to study PR, began to improve academically. “I did well this past year. I discovered I liked online learning.”

Still, high school was not devoid of struggles.

Life on the Circuit

After a particularly bad day, someone urged Ayden to write about her life. Eventually, she decided to see if others were interested.

Several outlets, local papers and foreign media and organizations, wrote about her story. Once she got a few bites, Ayden began doing what she describes as basic media relations, pitching her story and herself for interviews.

You’re reading about Ayden in PRNEWS because in spite of her difficult life, she wants to advocate for adoption, particularly from China.

“I want to be the voice for that little [adopted] girl who’s struggling,” she says. In addition, Ayden wants to help parents starting the adoption process or who have adopted and are searching to understand “what their kid needs.” She and the Lincolns have first-hand experience.

Mainstream Awareness

And you’re reading about her because she wants to raise awareness with mainstream media.

We’ve had limited interaction with Ayden. Still, we feel comfortable describing her as a ‘go-getter.’

For example, to better learn about PR, Ayden interned at a local PR firm as a high school senior. As a result, PR jargon slips into her vocabulary.

When Ayden came to us, she was targeting 35 PR firms, seeking pro bono help. In addition to no response, she’s received variations on the following:

- ‘Sorry, we’re not taking new pro bono work.’

- ‘We’d like to help, but we don’t have experience in [adoption PR].’

- ‘We can help, but we charge $10,000.’

As we noted, Ayden’s story prompted us to ask brand and agency communicators how they decide what pro bono work to take on.

With any question journalists ask, several sources politely decline to speak on the record. Others never respond. However, for this article, the rate of no responses and declines were higher than usual, which was surprising. Fortunately, several companies and PR firms told us about their decision process for pro bono work.

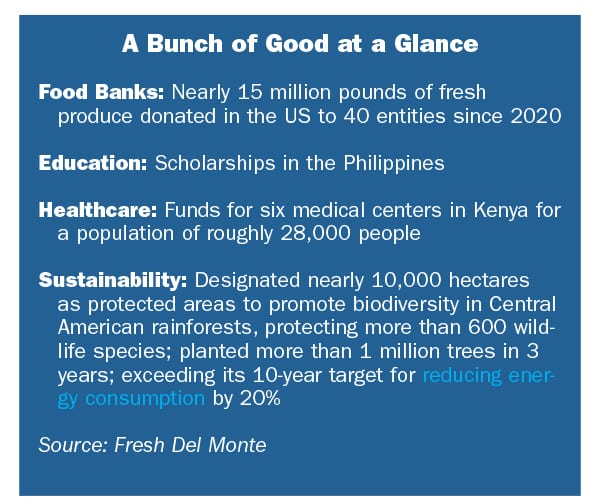

Pablo Rivera, VP of marketing at Fresh Del Monte, the North American distributor of fruits and vegetables, says the company’s CSR activities track with its ethos, a theme we heard often in interviews about pro bono work.

He describes Fresh Del Monte’s month-old CSR effort, “Bunch of Good,” as “the essence of who we are as a company.” In fact, Rivera tells us, the name “Bunch of Good” is an unofficial motto of the company.

Besides doing good for the planet, “our products simply taste better [when consumers] know the ‘Bunch of Good’ that is associated with our produce,” Rivera says. This led Fresh Del Monte to bolster transparency about its charitable activities and offer consumers a chance to join its ‘Bunch of Good’ coalition.

Another theme we heard often is that there are so many good causes that merit support that it’s difficult to choose. Fresh Del Monte is the fortunate exception. Its CSR work encompasses food safety, climate change and the well-being of its workers and partners, Rivera says. Its activities include education funding, food bank donations, supporting medical facilities and donating land to promote biodiversity and protect wildlife.

For Bunch of Good, “we opted to feature several programs to ensure we resonated with a wider audience,” Rivera says. Still, to give shape to the effort, Fresh Del Monte emphasized sustainability as an overall theme.

As you can imagine, CSR in a global company the size of Fresh Del Monte–its quarterly sales typically exceed $1 billion–includes many decision-makers.

Departments involved in creating the Bunch of Good campaign included sales, marketing, sustainability and the entire global leadership team, including its president and COO Yousseff Zakharia. Rivera, though, emphasizes the importance of internal communication when executing an effort like this, since “the entire company [is needed] to bring a campaign like this to life–packaging, operations, legal, product management, etc.”

Brian Lowe of BML Public Relations runs a small PR firm in suburban NJ, a short distance from NYC. His firm’s stance is that pro bono work is best when it comes from the heart and is a passion project.

“As communicators, we’re in a great position to share stories.” In addition, he feels there’s an obligation on business to give back. On the other hand, “there are only so many hours in a day…so we make sure that we have some love for the causes we choose.”

For example, the firm works pro bono for the ARC of Essex County, which supports people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Lowe is friends with a married couple who “have a terrific daughter” with disabilities. The couple approached Lowe and asked him to get involved in the ARC. Once he did, Lowe found the organization “was incredible…and I said, ‘Hey, [my firm and I are] going to help these guys tell their stories.’”

On the formal side, the firm also does paid work for nonprofits. “When we do that,” he says, “we always offer some sort of discount,” based on factors such as the goal and scope of the work. The firm usually will “find a way to make things work” with nonprofits, “because at the end of the day, we want to tell good stories and make an impact.”

As we found with all those we interviewed, there’s at least some formality in Lowe’s firm’s process. For example, when the firm’s slamming on a deadline, it’s unlikely it will have the bandwidth to entertain pro bono work. “That’s the sad part of pro bono work,” Lowe says. “You want to help everyone and you can’t” in part, because you lack the budget and/or the expertise in a particular area.

Still, in addition to the ARC, the firm will do one-off pro bono work for some organizations that approach it.

You Can’t Help Everyone

Similar to Lowe, Anna Crowe, Crowe PR’s CEO and founder, says, “There’s no shortage of incredible people doing great things. That’s the tough thing; you want to help everybody, but you can’t.” Still, she agrees with Lowe. “ss professionals and business owners, it’s our responsibility to give back.”

When the San Diego-based firm began, it chose pro bono work informally. “When one of us heard of an important cause, we carved out time to help,” Crowe says. In addition, Crowe was approached to sit on nonprofit boards. In those cases, she says, “We’d help in some way, shape or form.”

Last year, when COVID-19 hit, the firm increased its pro bono work. “We were less selective…we were just trying to help keep clients’ [and other organizations’] doors open.”

Similar to Lowe, when Crowe speaks of pro bono she includes “cost-based” work the firm does for small start-ups in addition to unpaid activities on behalf of an organization.

As the firm grew, though, the pro bono decision process became more formal. When thinking about pro bono work, Crowe says, it’s important to decide what you want your contribution to be. Is it digital work? Media relations?

In addition, the causes you pick must align with the firm’s core values. “That authenticity matters. There’s got to be a why behind your choice” of a pro bono cause. Without that, she believes, “it’s easy to take on too much and then you run into a shortage of time...[so] finding that balance” between paid and pro bono work is critical.

A Formal Process

This year, Crowe formed a committee of roughly seven employees to oversee its pro bono work and other CSR efforts, such as volunteering or mentoring a PR student. One of the committee’s duties is surveying staff members periodically about causes that are important to them and how much time they want to devote. In addition, employees are able to bring causes and organizations to the committee and management. “That doesn’t mean we say yes to everything, but we certainly want to consider issues and organizations that are important to our team,” she says.

During a given quarter, Crowe PR will support one to three pro bono clients. Like the pro bono work BML does, Crowe PR’s efforts vary from short, one-time partnerships to a year-long project. When Crowe PR is unable to help, it tries to recommend two or three firms who can.

Importantly, don’t forget to do internal PR after you’ve chosen a cause, Crowe advises. The more staff members are aware of pro bono work, the more they’re likely to amplify the message on their social channels and help the nonprofit. And it’s also a matter of transparency. “Make sure everyone knows what you’re doing and can serve as a voice” for the nonprofit and your organization.

Ayden Waits

As for Ayden, she continues to search for pro bono help. Those we interviewed advise that she network with communicators to figure out her next step. “Tapping other peoples’ networks is the fastest way to find somebody who can support your cause,” Lowe says. In addition, he suggests scouring profiles to find PR pros who are pro-adoption, perhaps someone who was adopted.

Similarly, Crowe urges Ayden to reach out to cause organizations. She should seek a mentor and ask a lot of questions. “I find that by asking questions you can avoid a lot of pitfalls. For the most part, people are very willing to share.”

Crowe also recommends Ayden look within herself. What are her strengths and weaknesses? There are a lot of exercises she can do it to determine this, Crowe advises. Does she want to be a spokesperson or write collateral and let someone else speak? “Again, speak to CEOs or executive directors and find out what’s working well for them,” she says.

For things that Ayden determines are not her strength, including fundraising, she needs to find others who are and share Ayden’s desire to “bring this vision and mission to life. Here’s hoping the best for her.