In theory, few professions are better-suited to entering and winning industry awards and contests than communicators. After all, the PR pro’s stock-in-trade is working with words and images. Creating messages that resonate with audiences is their daily gig. Completing a contest entry form and making sure it’s memorable should seem like a busman’s holiday for PR pros.

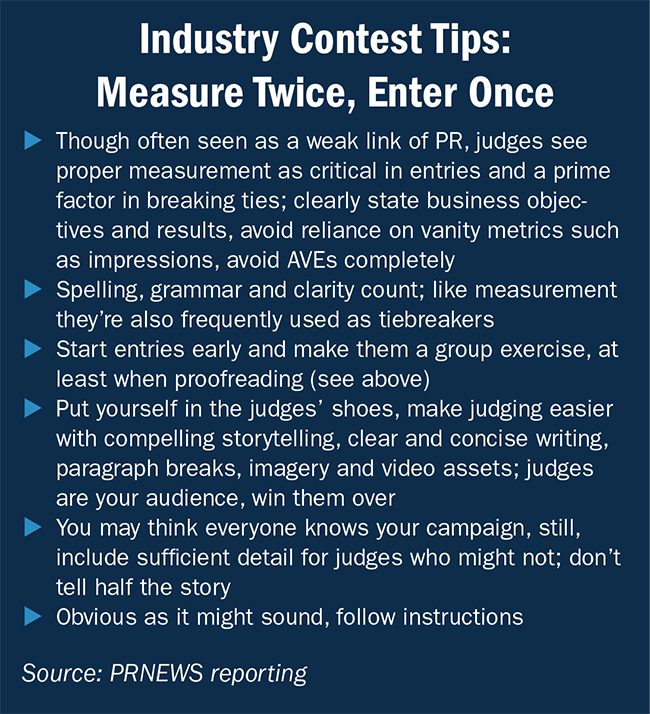

While veteran contest judges agree with the above premise, they also tell us more than a few entries fall short of the mark. Moreover, two oft-dismissed items, spelling and measurement, remain vitally important, judges say.

Last, if you're seeking quick fixes or silver bullets that will help you win contests, look elsewhere. Though there are useful tips throughout this article, it's clear that winning begins with a time commitment.

Assuming the best teacher is a mistake, let’s consider first some of the judges’ dislikes.

Follow Directions

Their pet peeves include contest entrants who fail to follow instructions. “When an application says ‘use 11-point font, and submit a 1-page overview.’ And then you open up the entry and it’s in 9-point font and the summary is a page and a half…come on, follow instructions,” says Robert Hastings, EVP, communications & government affairs at Bell, formerly Bell Helicopter, and a veteran judge.

In addition, flabby and uninteresting writing are downers for judges, says Curtis Sparrer, principal and cofounder of the firm Bospar, who’s judged contests, to say nothing of entering and winning a slew of them. “Sometimes there’s a lot of cutting and pasting without much thought given to the question [an entry is] addressing,” he says.

Poor Writing

In the same vein, Kevin Wong, VP, communications at nonprofit The Trevor Project, dislikes entries that lack “quality storytelling.” Wong's taken home a bevy of honors and served as a judge.

And then there are garden-variety sloppy mistakes, such as misspelled and missing words.

For Hastings, such mistakes sometimes indicate a lack of effort. “You can spot that quickly,” he says. Wong agrees. As such, “regardless of who drafts a submission, I always recommend a review process that includes a senior communication leader.”

Spelling Still Counts

In this moment, when spelling and grammar sometimes barely exist, PR contest judges see things differently. Samara Finn Holland, EVP, growth & strategic initiatives, Kaplow Communications, says, “I consider spelling, grammar and writing quality when judging…most of the time, the judging and entry guidelines are clear that writing quality is considered.”

Both she and Wong say it’s rare to find many proofreading errors in entries, though all of our judges admit seeing them. “When there are significant errors, it’s often indicative of a larger problem: a confusing and unclear entry,” Wong says.

While it’s never good to submit sloppy work, there’s an additional danger. When judges face a large number of entries, sometimes they’ll look to prune the pile quickly. Bad writing, spelling and grammar errors can prompt a quick exit from award consideration, several judges tell us. “When competition is fierce and a judge needs to make a tough decision about what programming should be recognized with an award, glaring errors are a deciding factor for me,” Finn Holland says.

Surprise: Measurement's Important

While our sample size is far from scientific, judges were uniform in their view of something often considered PR's unwanted stepchild: measurement. It's become “a make-or-break section” in contest entries, says Finn Holland.

Hastings has a similar take. He concedes “measurement is hard” and takes time, yet “it doesn’t have to be expensive.” Most important, a lack of solid metrics helps judges quickly eliminate entries, he says.

Indeed, a pet peeve of Finn Holland, besides “glaring typos and a lack of supporting materials,” is an entry without qualitative impact. “The PR industry has evolved so much that when it comes to quantitative results, vanity metrics no longer cut it.”

For example, she dismisses applications that rely on numbers of impressions because they “don’t tell much of a story…I want to see how perception was changed, how new audiences were reached, or how communication efforts impacted overall sales/product performance.”

Likewise, Hastings frowns on impressions. “They’re only directional,” he says. A story in a magazine can garner a large number of impressions, he says, “but if your target audience doesn’t read that magazine,” they’re not useful.

'A Litmus Test'

Hastings, like several other judges we spoke with, decries applications that use AVEs. “There’s no science behind them,” he says.

When Sparrer, the San Francisco Bay Area PRSA chapter’s PR Pro of the Year in 2020 and 2021, is deciding whether or not to enter a campaign in a contest, he begins by looking at its business results. This helps separate good work from a potentially award-winning entry, he says. An award winner, Sparrer adds, is one that “moves the industry…it’s a campaign that others want to emulate.”

Similarly, Finn Holland considers measurement “a great litmus test when debating whether to submit a program or not–if you’re struggling to make the case of what the work achieved and why the impact was important, you probably shouldn’t submit it.”

No Way

By the same token, when judging, Sparrer is suspicious when an entry lacks substantive business results. It’s “a huge red herring” in contest entries. “Look, if you don’t have business results, you’re doing PR for decoration.”

There’s another pet peeve that mixes arrogance, failure to follow instructions and measurement. For example, an application that skimps on analytics because the campaign resulted in an article in a mass-media publication.

What to Do

While we looked for fool-proof tactics that can guarantee your entry will stun judges, none were offered. On the other hand, there's good news. The thesis at the beginning of this article holds: PR pros have the skills for crafting strong contest entries. As such, some of the ideas below derive from standard PR practice.

View Judges as Your Audience

Says Hastings, “Your job in PR is to sell; your job is to take an audience, understand the audience and give it information and drive it toward an outcome, change behaviors and beliefs.” Approach a contest entry the same way. “If you don’t think of judges as your audience, you miss the mark right off the bat.”

As a senior judge for PRSA, Hastings counsels incoming judges that an entry “should win you over.”

The biggest thing he seeks in an entry “is the science behind PR....I’m looking for evidence that you’re not just stumbling through and getting great results.”

Objectives

So, he wants to see objectives and research “to establish where you started from…and measurable outcomes” that tie back to the “objectives you started with…it’s that simple.” Adds Wong, entries must “clearly tie any strategies and tactics back to your goals.”

Wong feels so strongly about this that he urges entrants consider an application as a guide only. “Regardless of the submission prompts, find a way to articulate your goals, how your strategies and tactics worked toward each goal and the results you achieved,” he says.

Time is of the Essence…

Though contests can build and burnish reputation, entry forms sometimes are delegated or done quickly. “It’s obvious if an entry is rushed, not proofread, or assigned to a more junior professional,” Finn Holland says, sharing the view of other judges.

The best practice, at least for Sparrer, is “hopping on a contest way ahead of time…almost as soon as it’s announced.” Similarly, for Wong, “Given the amount of time it takes to collect ample information, plus the time it takes to complete rounds of approvals, it’s important to start award entries far in advance.”

Time and Time Again

While it’s not a great revelation, doing applications well takes time. Wong recommends having a group work on award entries, with a point person leading the effort. The point person gathers relevant information, pulls in stakeholders and partners and then drafts the entry, he says. In addition, the point person manages the review process with stakeholders and a senior communication executive, Wong says.

A time-saving tip that Wong employs is compiling campaign recaps. With such material in hand, it makes it easier for the team “to have enough information to complete award entries,” he says.

Similarly, though Sparrer tells us he’s “the principal writer” of Bospar’s entries, it’s a team effort. He has a videographer working with him on summary videos and other members of his team help him collect data and research for entries.

No Substitute for Time

For Sparrer, there’s no substitute for investing time. He admits, “I drive people nuts drafting and re-drafting” entries. In addition, when industry contests ask for a video that summarizes an entry, he spends “weekends” agonizing over edits. He also reads copy for entries out loud until it sounds right. Ditto for narration that accompanies summary videos.

An insight he shares is that he’s constantly thinking of how a judge “might disagree with what I wrote.” As such, when he’s judging, he looks closely at budget details. “When I see an impossibly low dollar figure for a campaign budget, I’m very skeptical.”

In addition, Sparrer tries to make entry copy “as strategic and detailed as possible.”

Again, the time investment. Hastings and Sparrer advise having several people read and proof entries before they’re submitted. For example, Hastings has a “four-eyeball rule” on any content that leaves his shop. Sparrer has people inside and outside Bospar, including former judges, reading his draft entries.

Entertainment Value

While Sparrer’s approach undoubtedly is time-intensive and he advocates sparing few details—"Show the sausage-making in all its glory,” he says—he also emphasizes an entry’s entertainment value. “There are so many people entering. You have to make it fun and entertaining to stand out…it’s like a TV show. You have to grab [the judges’] attention.”

Watching his summary videos illustrate Sparrer's point. These two-minute videos are well-edited and tell a story. Moreover, they're fast-paced and loaded with useful, attractive images. In addition, they don’t make judges work hard. He avoids creating summary videos that are heavy on text.

‘Devils in the...’

Following from Sparrer’s sausage-making comment, several judges tell us they’re sometimes lost when reading entries that lack sufficient detail. The writer is knee-deep in the campaign and assumes, incorrectly, that judges are too. “Don’t assume…and know your audience,” Hastings says.

Similarly, Wong decries entries that lack “enough context” and those that “only share half the story.”

One way to overcome leaving judges in the dark, Finn Holland says, is including details about your research and strategy. “I find when categories or products may be niche or not universally known, the research and strategy sections…can work hard in educating the reader on what they need to know to understand the entry and impact of the work.”

In Sum

Says Finn Holland, “Put yourself in the judge’s shoes before hitting that submit button!” Accordingly, it’s what and how you present it. For Wong, this means avoiding huge blocks of text. “To make judges’ jobs easier, we use section headers to make our points digestible,” he says.

And clear writing is a must. “The best entries clearly communicate the effectiveness of their campaigns,” Wong says

.