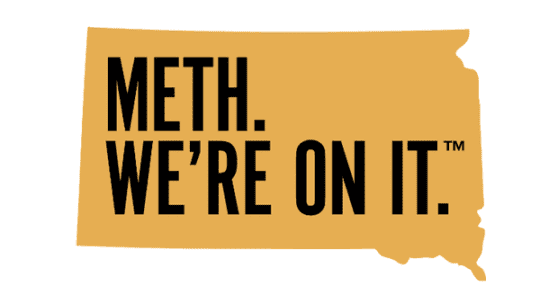

South Dakota's PR campaign around the state's methamphetamine epidemic accomplished what it set out to do—create awareness around a state-wide health crisis. But the play on words, "Meth. We're on it," superimposed over pictures of teens, farmers and older women, also ignited a debate about the high cost of quick-won awareness, and whether it's true that "there's no such thing as bad publicity."

Is 'awareness' enough?

Before digging into the many well-founded criticisms of this campaign, a look at those who praised its effectiveness is quite telling. After all, we're talking about it here, aren't we? The New York Times covered it, describing the campaign as "raising eyebrows" in the headline and pointing out that its controversy-grabbing tone was intentional.

“That was the tone going into it, looking for something that would be edgy and that would be able to cut through clutter in advertising and social media,” Laurie Gill, the state’s secretary for the Department of Social Services, said an in interview on Monday night.

“I would say that we did expect a reaction,” she continued. “It’s a play on words. It’s sort of an irony between healthy South Dakotans, that probably very much aren’t meth users, saying ‘Meth. We’re on it.’ The point is everybody is affected by meth. You don’t have to be a user to be affected by meth. Everybody is.”

Hey Twitter, the whole point of this ad campaign is to raise awareness. So I think that’s working... #thanks #MethWeAreOnIt

⬇️⬇️⬇️https://t.co/hopPjqa95w

— Governor Kristi Noem (@govkristinoem) November 18, 2019

On Twitter, many echoed that, between the virality of the campaign and the subsequent awareness it generated, it was a success.

The South Dakota meth ad campaign is doing exactly what it supposed to do

— Chris (@chrstphr_woody) November 18, 2019

I hope you've all figured out that South Dakota's ad agency knows exactly what it's doing and you're giving them the attention they wanted? (If their slogan had been of the "Don't do meth; it's bad for you" ilk literally no one would be aware of SD's anti-meth campaign today.)

— David Jarman (@DavidLJarman) November 18, 2019

Also, JUST TO BE CLEAR, it's not a joke. Here's the governor announcing the new campaign and website: https://t.co/YQHJMAnG3H

— Mike Baker (@ByMikeBaker) November 18, 2019

As implied above, the journey this campaign intends to take us on begins with us thinking it must be a joke because it is so absurd, followed by us realizing that it is indeed not a joke, concluding with the realization that the state's meth epidemic is also no joke.

It's a long play, requiring a social media audience with traditionally short attention spans to not only process the double entendre, but subsequently click in for more information on South Dakota's program to actually fight the epidemic. What's abundantly clear is, with all the scrutiny placed on this campaign to deliver on its intentions, the social good effort can't stop at "awareness."

Gimmicks invite scrutiny into resources

As a national campaign is often a hefty spend, questions about this campaign's reach invited critics to look into its cost.

South Dakota taxpayers paid $450k for a new anti-meth PSA campaign. And here's what the state came up with https://t.co/1MATJPBULv pic.twitter.com/bsZKkXCPNL

— Lachlan Markay (@lachlan) November 18, 2019

Though the state's 2020 budget also includes $1 million for meth treatment services and more than $730,000 for school-based meth prevention programming, $450,000 has been regarded as a hefty price tag for the end goal of "awareness." According to the Times' piece, that number will continue to grow as the campaign continues.

"The contract called for up to approximately $1.4 million to be spent on the campaign, according to state records," the Times reported. "The proposal outlined a multi-pronged effort that includes television advertising, t-shirts and stickers all featuring the tagline. Ms. Gill said the campaign was slated to run through May and that the state could spend less than the total $1.4 million if it wanted to curtail the campaign."

In the top comment on Gov. Kristi Noem's Facebook video announcing the campaign, one resident posted a photograph of the budget for this campaign and demanded an explanation:

It's clear from the backlash to this campaign that no matter how effective the slogan was at increasing awareness to the state's meth epidemic, the pressure is on to see that awareness generate some genuine return on the spend—in this case, a decrease in the number of meth-related convictions plaguing the state and some demonstrable data around the amount of residents seeking help.

When treated as a stand-alone KPI on social networks like Facebook, awareness often becomes a vanity metric, a top-of-funnel spend for advertisers hoping to wow senior leaders with a large number that doesn't translate to conversions, or in this case, recovery. That said, whether South Dakota's provocative campaign can effectively shock residents into action and encourage folks to become stewards for the health in their families and communities, remains to be seen.