Anyone who has studied crisis communications knows, “he/she who speaks first owns the narrative.” Once bad news breaks, whether it is a self-inflicted crisis, accident or natural disaster, there’s a sequence that all crises follow. Something happens, the news media finds out about it and starts asking questions, and whoever answers those questions first gets to shape the narrative of what happened.

When Southwest Airlines cancelled thousands of flights over the Christmas holidays, leaving passengers and crew stranded all over the U.S., it was the head of the Pilot’s union that first started answering questions and pointing the finger at the airline’s outdated computer system that union members had complained about for years. The narrative focused the blame on corporate decision makers that failed to upgrade the system. As a result, the COO (CEO Bob Jordan was a no-show) spent many uncomfortable hours in front of a congressional committee hearing doing mea culpas and promising to overhaul the systems.

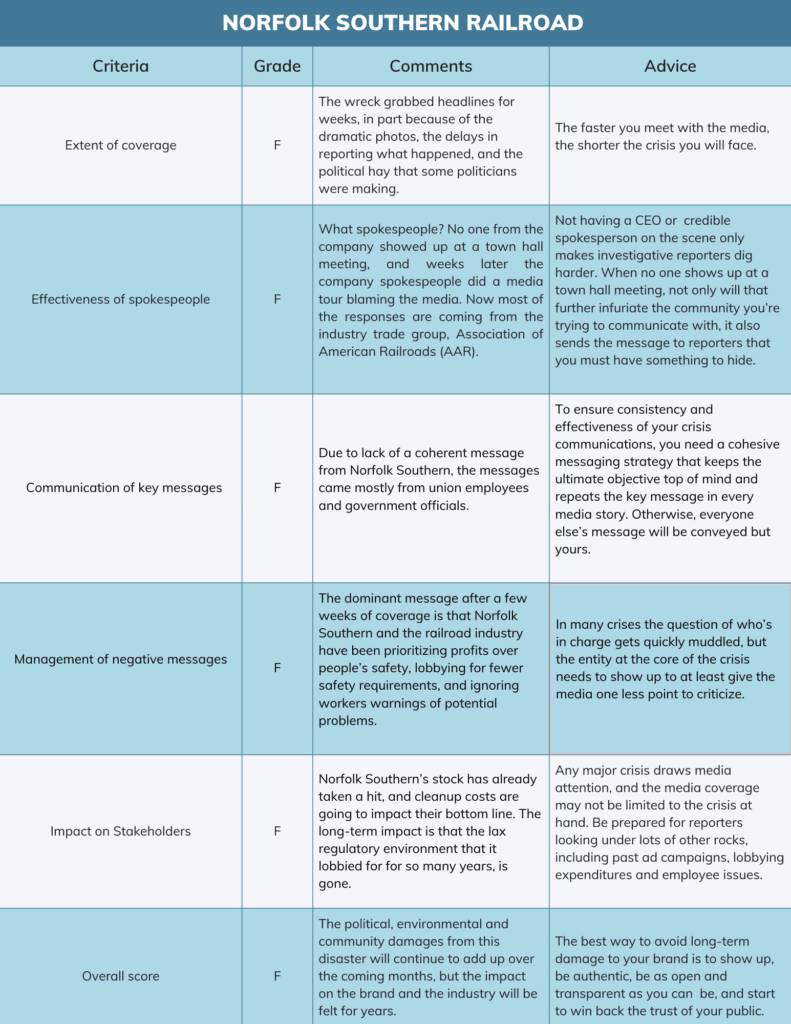

Norfolk Southern

A similar scenario is playing out in East Palestine, Ohio in the wake of the Norfolk Southern train derailment. The unions were quick to blame management, painting them as reluctant to invest in improvements and over-taxing the workers for the sake of profit.

Employees began leaking examples of the company’s lax safety policies to the media. Within days, elected officials called for hearings on whether the railroad industry sacrificed safety for profits. Reporters dug into the company’s lavish lobbying and advertising expenditures, intended to weaken safety rules. Compounding the problem, the company issued statements but failed to show up at a town-hall meeting, which infuriated local residents, who were happy to voice their complaints and concerns to reporters on the scene.

When the bad news didn’t go away, the company finally decided to speak publicly in what was seen as a “blitz,” designed to blame the media and politicians for misinformation.

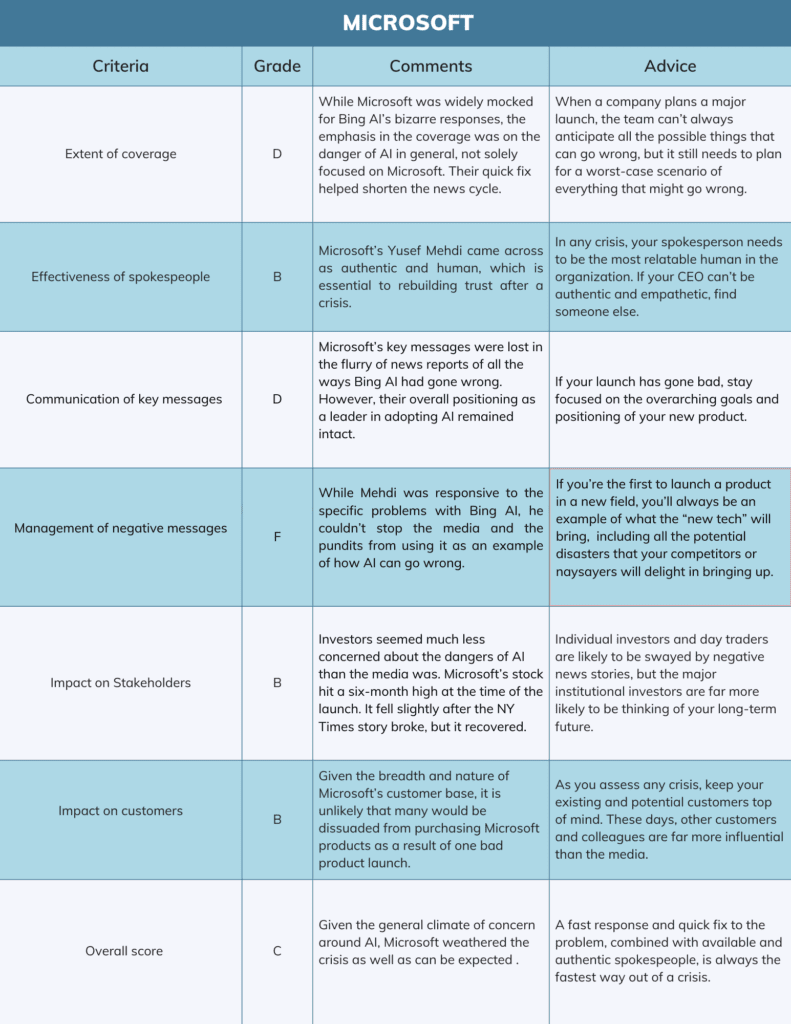

Microsoft

In contrast, Microsoft was quick to respond after an influential New York Times tech reporter had a troubling encounter with newly-revamped, AI-driven search engine, Bing AI. In what was seen as a major coup, Microsoft inked a deal with chatGPT developer Open AI and quickly incorporated AI functions into its moribund search engine Bing. The move was initially seen as a major threat to Google’s domination of search.

To make the new product more irresistible, Microsoft limited access to technology writers and influencers, including Kevin Roose of The New York Times.

But the praise soon turned to mockery when Roose got a little too deep into the bot’s brain, as it declared its love for him and suggested that his marriage was failing. The encounter was further publicized on The Times' popular podcast "The Daily" and quickly made national news. Additional news outlets reported other strange encounters.

Microsoft quickly released a blog post explaining that it hadn’t anticipated reporters having such lengthy conversations with the search engine, and placed limits on the types of interactions one can have with Bing AI. Microsoft Vice President Yusuf Mehdi, a corporate vice president at the company, was on the phone with reporters within days, admitting that they hadn’t anticipated every scenario, and were still figuring out what the AI engine might do.

While the story hasn’t gone away, Microsoft’s swift response seems to have shifted the focus away from Bing AI to the broader issues around AI and search.

Katie Paine is founder and CEO of Paine Publishing