We’ve all heard and seen the media use the term “charm offensive” whenever a brand or a country pays lobbyists and PR agencies huge fees to attempt to improve a tarnished reputation.

And, in fact, for decades, many of these efforts worked. Think Tylenol, Nike’s labor problems, and Martha Stewart going to jail. Eventually, by admitting guilt, changing policy or offering greater transparency, good PR plus the passage of time can work miracles.

Those days are officially over.

Today, between the speed of the news cycle, the polarization of the populace on big issues, and a generation of consumers who, thanks to social media, are much more aware of environmental and human right abuses, trying to fix a bad reputation with a good charm offensive isn’t working very well.

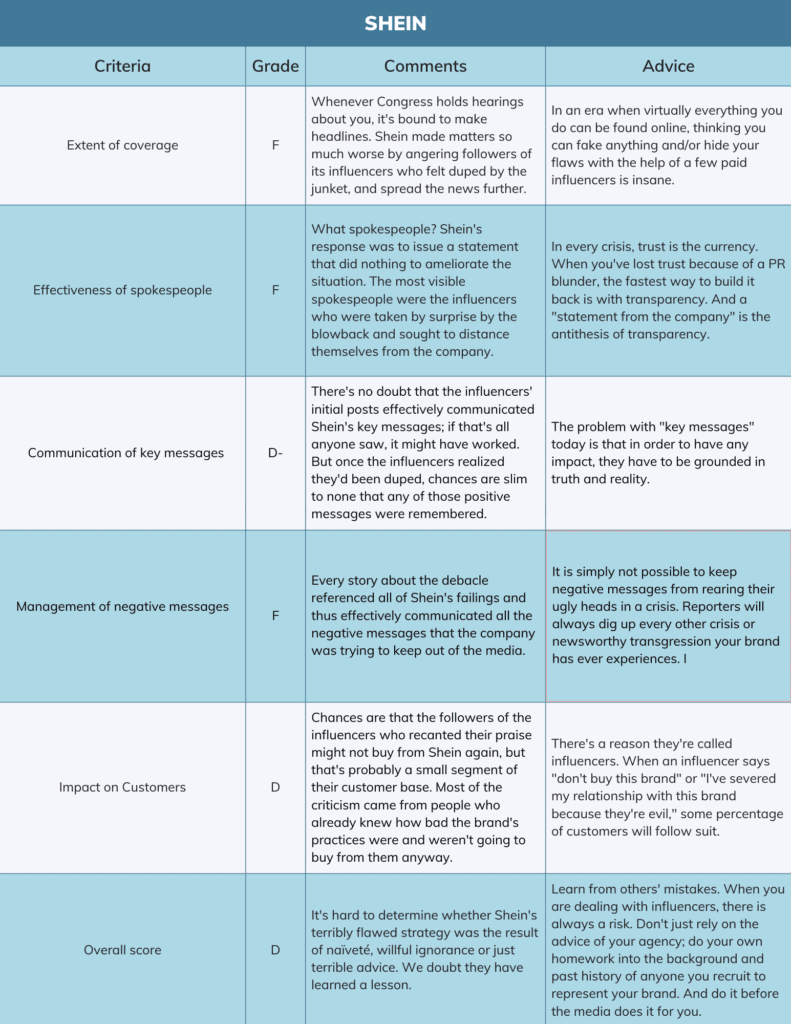

Shein

In June, Shein, known for its ultra-cheap fast-fashion was the subject of a congressional report that accused it of using forced labor to make its clothing. The report found that a key element of the Shein business model enabled it to avoid import duties and inspections and thus skirt the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) that prohibits clothing made from forced labor from being imported.

At the time, the company had also announced its intent to take the company public. So naturally, a month later, Shein launched a classic “charm offensive” to improve its reputation. The goal was to counter the negative narratives around their manufacturing and labor issues.

Shein’s solution was to recruit a group of fashion-focused social influencers and invite them on all-expenses-paid trip to China to tour Shein’s “manufacturing” facilities. The plan was that they would provide lots of swag and photo ops to charm the influencers into saying nice things about the brand. And the influencers complied, posting numerous fun videos and countless images showing a spotless factory and happy workers.

But the rest of the online world wasn’t having it, and the fierce social backlash took the influencers by surprise. The “factory” was, in fact, Shein’s “Innovation Center,” and the influencers were seen as paid shills for a horrible company. And almost every post included references to forced labor, human rights violations, Shein’s habit of stealing other designers' work and the peddling of clothing made with potentially hazardous materials.

Not exactly the key messages they hoped to convey.

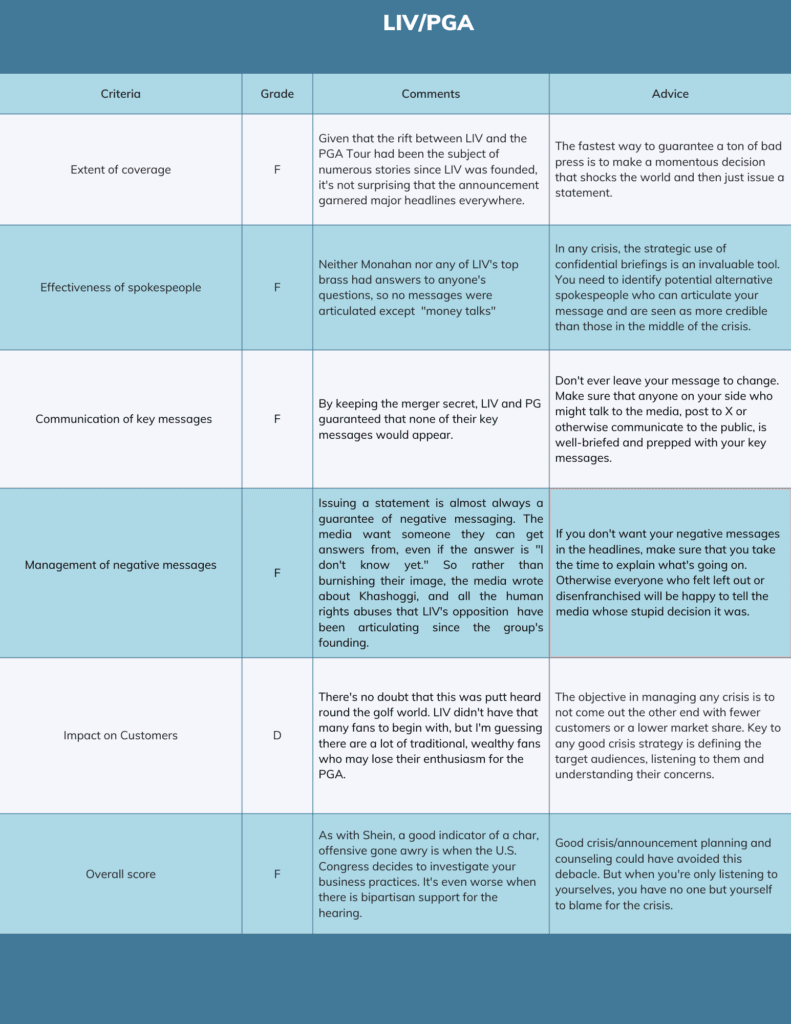

LIV and the Saudi Sportswashing Program

The Saudi Public Investment Fund (aka sovereign wealth fund) has some $600 billion in its coffers and is free to spend it on whatever the kingdom sees is in its best interest. Clearly it sees sports as a great way to get positive press.

While best known in the sports world for buying up European football (aka soccer) teams, in 2021 it decided to make a major investment in golf, creating the LIV tour to compete for players with the PGA Tour, America’s best known golf organization. The ensuing brouhaha generated numerous vitriolic statement from highly visible golf superstars like Rory McIlroy.

The PGA responded by banning players that took the LIV money. PGA’s commissioner and top spokesperson Jay Monahan portrayed LIV as the PGA’s mortal enemy and almost every story included references to the Saudi’s terrible human rights record, their connection to 9/11, and/or the killing of Washington Post reporter Jamal Khashoggi, whose death the U.S. National Intelligence tied directly to Saudi’s Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman.

That all changed in June, when seemingly out of the blue, PGA and LIV issued a joint press release on their upcoming “merger.” The as-yet-unnamed and undefined new organization would be run by the head of the Saudi Public Investment Fund, but current members of the PGA board would become members of “Newco’s” board. And that’s about as much as anyone knows about this new organization.

The news was met with horror by many of the PGA’s faithful fans, and also by families of 9/11 victims. But by far the most frequent term to describe the deal was “sportswashing,” the practice of using popular sports and star athletes to charm the governments and other influencers into forgetting about your human rights abuses and other reputational issues.

And, as we saw with Shein, it didn’t really work.

Criticism was loud enough to cause bipartisan outrage in Congress and ultimately a highly publicized public hearing on the topic by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

The Senators were clearly not charmed, and the deal has yet to be finalized.

Katie Paine is founder and CEO of Paine Publishing