It’s too early to know what historians will say about last month’s violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. As lawmakers gathered Jan. 6 to certify the 2020 U.S. presidential election results, an angry, weapon-wielding mob breached security, stormed the historic building and came within feet of entering the Senate chamber. The rioters, 400 at least, were a portion of some 25,000 people who attended a rally to protest the legitimacy of the 2020 election.

Rioters occupied the site for several hours, making their way into the House chamber and members’ offices. Members and staff, meanwhile, were hiding in the Capitol, fearing for their lives. As we go to press, 140 police officers are reported injured; one was killed and two have committed suicide. 400+ arrests were made, with more expected.

A few hours later, the building was cleared. Lawmakers who were able went back to work; 147 voted to overturn some results of the election; this after 62 challenges to the contest’s legitimacy were rebuffed in courts.

Corporate Reaction

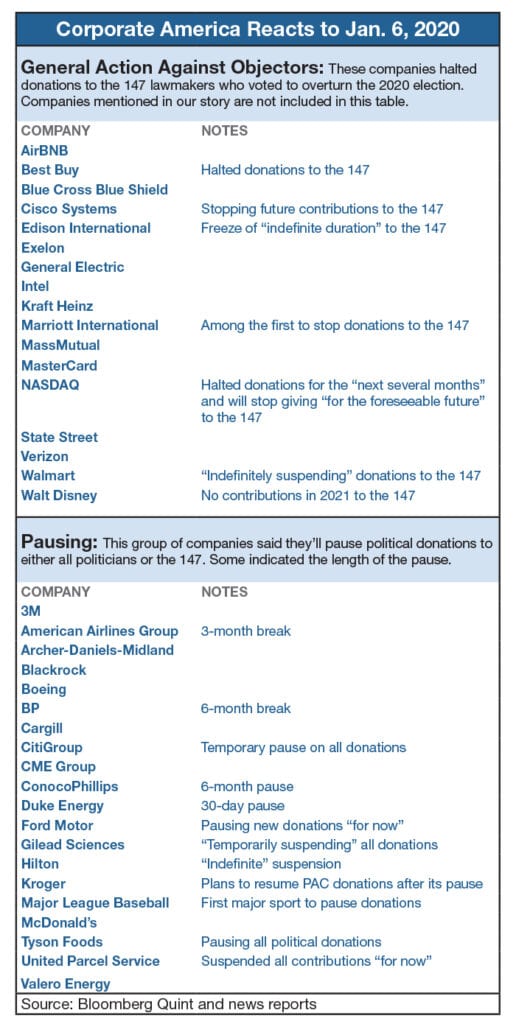

One thing economic historians likely will include in their accounts is the reaction of some of the country’s largest companies. It started with several blue-chip firms denouncing the violence and the 147 lawmakers who voted in favor of overturning election results.

Then the movement gained speed. Powerhouse firms from Coca-Cola to Dow Chemical and Nike reconsidered, paused or stopped, at least for the moment, donations from companies’ political action committees (PACs). Some PACs halted all political donations, others targeted certain lawmakers.

One company shut its PAC altogether.

2021 Should Be Fun

Related issues for communicators run the gamut from explaining why their company funded politicians who voted to hinder the peaceful transfer of power to whether the brand will resume funding, of whom and when.

Related issues for communicators run the gamut from explaining why their company funded politicians who voted to hinder the peaceful transfer of power to whether the brand will resume funding, of whom and when.

In addition, the situation exposed yet another activity of corporations, their political donations. Stakeholders, including customers, employees and shareholders, likely will pay more attention to this somewhat opaque activity.

PR pros, according to communicators we spoke with, will need to fit political giving into a larger narrative. With the social, political and economic upheavals of 2020, stakeholders and critics are expected to increase scrutiny of corporate activities in 2021 (see page 7, chart p. 13). This includes political giving, diversity and sustainability (see pages 4 and 16).

PAC donations are just one way corporate money is funneled to politicians, political parties and other causes. Companies can donate unlimited amounts to super PACs, for example, and industry PACs. In addition, CEOs can personally donate to candidates.

On the other hand, though corporate PACs are limited to donating $5,000 to a member of Congress ($10,000 to a candidate), the money adds up fast. The AT&T PAC, for example, donated in excess of $3 million during the 2018 election. Google’s NetPAC disbursed nearly $2 million during 2019-2020.

Moreover, the speed at which top-flight companies announced their PACs would halt or pause the flow of money was significant (see story on page 14). And the number and quality of companies doing so was impressive (see chart at right).

Predictable?

For some communicators, the reaction was not a large surprise. Suspending PAC giving, they argue, stems from what we noted earlier: 2020 pledges on diversity and other issues set the stage for a reset in 2021.

“Actions, as the saying goes, speak louder than words,” Prudential Financial CCO Alan Sexton tells us. That adage, he adds, will ring true even more in 2021. “What companies do, or don’t do...is what will be most scrutinized in this environment of distrust and misinformation.”

Businesses and organizations, he adds, “will be judged based on the progress they can show [on issues like diversity], and the accomplishments they can point to” (see story, p.5).

Broad Picture

Licy Do Canto, managing director of APCO Worldwide’s Washington, DC, office and its mid-Atlantic region, agrees.

“What I think is happening is part of a much broader narrative...You’re seeing a reassessing of the role of corporate America...the next chapter,” Do Canto says. The smart companies, he says, will realize “this is not a temporary moment.”

Indeed, two days before the Jan. 6 violence, more than 160 NY-based business leaders sent a letter to president Trump, urging a peaceful transition. One of its signatories, Kathy Bloomgarden, Ruder Finn’s CEO, tells us Jan. 6 “was a turning point for many companies...spurred by both employees and customers, for business leaders to act as corporate citizens.”

Of course, signing such a letter comes with responsibilities. Days before the Jan. 6 violence, Microsoft employees questioned company president Brad Smith, who also signed the letter. Employee Jake Friedman tweeted that Microsoft’s PAC supports politicians who contested election results (see right).

Under the previous administration, Do Canto says, CEOs and companies got pulled into the political sphere “whether they wanted to or not, from the very top of government.”

That’s changed, so far, under the Biden administration. “What hasn’t changed,” he says, “is for corporate America to take a position decisively on something...It’s not just employees demanding that; it’s also shareholders.”

In addition, he says, companies are “paying more attention” to how their money talks and “what it’s communicating” about corporate values. Previously, companies’ communication “was all about promoting a particular product or service. Now that microscope is pointed” inward, Do Canto argues. Companies, he says, are asking ‘How does what we do on giving, diversity and the environment reflect back’ on us?

Make no mistake, for many companies, the PAC action is more than altruism. One consideration stems from the question: How will our company’s stance on social and political issues influence profits?

BlackRock Heal Thyself

Indeed, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, a leader in the corporation-as-societal-partner camp, frames CSR within a financial context. In the 2021 version of his yearly letter to CEOs, he stressed the policy and financial importance of companies disclose more information about their reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions. Besides being good policy, Fink said the issue is important because of financial risks to investors.

Perhaps illustrating what is yet to come as stakeholders pressure companies to act their values, Fink, who runs the world’s largest asset management firm, received a slightly embarrassing letter Jan. 25. In it, 24 investment managers, who oversee more than $1 trillion in funds, demanded more information about BlackRock’s political giving. Will the company offer more insight into its political donations? In addition, the letter asked whether or not BlackRock will halt donations to the 147 who voted to overturn the election. Fink was one of the first to condemn Jan. 6’s violence.

At press time, other companies were making news related to the 147 and former president. Sephora, the cosmetics giant, ended its relationship with 29-year-old influencer Amanda Ensing (1.4 million followers on Instagram) over offensive social posts, including several related to the Jan. 6 events.

In another item, grocer Publix was facing boycott threats on media reports that a daughter of the chain’s founder donated $300,000 to the Jan. 6 “Stop the Steal” rally.

What’s Next?

One question is where brands go from here. It seems clear some PR pros will need to craft messages that their company’s PAC is resuming donations. PACs might even restart donations to some of the 147 who voted to overturn the election. A look at how companies communicated their PAC actions leaves plenty of room for interpretation.

Some paused donations to both Republicans and Democrats to reduce political tension in a badly divided country.

“I can confirm that we have suspended PAC contributions to all candidates to allow for a comprehensive review of our approach,” Prudential Financial’s Sexton tells us. “I don’t have anything else to add at this point.”

Others, such as Nike and AT&T, had targets. They suspended donations to the 147 Republicans (8 senators and 139 House members).

Several hedged. For example, Facebook, Google and Microsoft said they’d pause political giving and review donation policies. Similarly, television giant Comcast, which owns NBC, and banking behemoths Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase made similar statements.

Amazon suspended donations to the 147, but said it will speak to those it supported and evaluate their responses “as we consider future PAC contributions.”

Others did not specify what they’d do during the pause. Some were vague about how long pauses would last. Several used language so they could resume PAC donations.

Google: No Donations

Of the tech titans, Google was the first to move beyond pausing. The search giant’s NetPAC said Jan. 26 it “will not be making any contributions this cycle to any member of Congress who voted against certification of the election results.”

Similar to the tech companies, Bank of America, FedEx and Wells Fargo said they are reviewing the situation.

One company, the brokerage Charles Schwab, decided to get out of the political donation business altogether. In a Jan. 14 statement, it announced its PAC will close immediately. The statement said the PAC will send remaining funds to Historically Black Colleges and Universities and the Boys & Girls Club of America, which it supported previously.

“In light of a divided political climate and an increase in attacks on those participating in the political process, we believe a clear and apolitical position is in the best interest of our clients, employees, stockholders and the communities in which we operate,” the Schwab statement said.

Schwab made its move reluctantly.

“It is unfortunate that our efforts to advocate for investors are now being purposefully misrepresented by voices on both sides of the aisle as something they are not. It is a sad by-product of the current political climate that some now resort to using questionable tactics and misleading claims to attack companies like ours,” it said. This was a not-so-veiled reference to an ad from The Lincoln Project, which incorrectly said Schwab, not its PAC, donated to the 147.

American Express sent a memo to all employees Jan. 11 to announce it was stopping donations to 22 House legislators who voted to “disrupt the peaceful transition of power.” None of the senators the company’s PAC supported voted to overturn the election.

The AXP PAC, similar to many others, is supported through voluntary employee donations. In some cases, board members also are permitted to donate to corporate PACs. Companies are permitted to cover some PAC expenses.

It’s The PAC Not The Company

Many companies use wording similar to the first line of the above-mentioned Schwab statement: “The Charles Schwab Corporation has not, and does not, contribute to lawmakers, political candidates or political parties. The Charles Schwab Corporation Political Action Committee (PAC), which is funded by voluntary contributions from employees and directors of Schwab, is the sole means by which any financial support has historically been offered to lawmakers.”

Hallmark’s HALLPAC blasted Sens. Josh Hawley ($7,000) and Roger Marshall ($5,000) for voting against the election and asked for its donations back.

Dow Chemical specified length in its statement. Dow said its halt in donations would last one term; for House members that’s two years, and six years for senators.

In addition, it said it will not donate to the re-election of any of the 147. Dow gave at least six figures to the Michigan Republican Partyyearly, including $1 million in 2017.

General Motorsdecided not to suspend or pause PAC donations. It released a statement through a spokesperson that said GM PAC will continue to review donations, as it’s done previously. “For 2021, as is standard in any contribution cycle, PAC contributions will be evaluated to ensure candidates align with our core values.”

A Light Lift?

Some critics contend pausing PAC donations now, well before the 2022 mid-term elections, is a light lift for companies. Though fund-raising is a non-stop effort in American politics, January during an off-year is not high season for donations. Some companies, these critics contend, will eventually restart their donation process, likely in the run-up to November 2022. The break between donations, these companies hope, will ease immediate pressure from stakeholders. They also note that large companies still employ lobbyists.

On the other hand, the PAC situation has some Republican politicians concerned. “I think you can safely say that Republican House incumbents who have relied on [donations from] business [political action committees] PACs are facing difficult situations,” a veteran GOP fundraiser told CNBC.

As a result, some Republican lawmakers are considering appealing directly to corporate CEOs for donations, CNBC reports. This maneuver bypasses company PACs. CEOs, as individuals, can give the maximum contributions to campaigns and affiliated committees, or an unlimited donation to House Republican super PACs, CNBC said.

This approach can work on the congressional level. About half of the CEOs of Fortune 100 companies donated personally to a candidate or party this cycle. It’s more of a problem with donations to presidential campaigns, however, as a donation paints a CEO and his/her company as a supporter of one candidate or another. At least on the presidential level, this is a reputation issue that few Fortune 100 CEOs desire to hurdle. Perhaps that’s why only six CEOs of Fortune 100 companies donated to either Biden or Trump.

Again, the question: What’s next? If you look at a transcript of Microsoft’s Smith explaining why PACs are vital, it seems clear at least some companies will donate again.

Communicators at companies resuming donations should be as authentic and transparent as possible about doing so, APCO’s Do Conto says.

On the other hand, Bloomgarden says, this moment has “accelerated the potential for a complete overhaul of donation policies.”

In two years, Do Conto believes, it will be more than, “‘Oh, there’s an election coming up.’” Instead, brands will assess and reassess “what the value [of political donations] is to our brand...and to who we are as a company as part of a broader discussion.”

Media Coverage of Brands’ PAC Actions

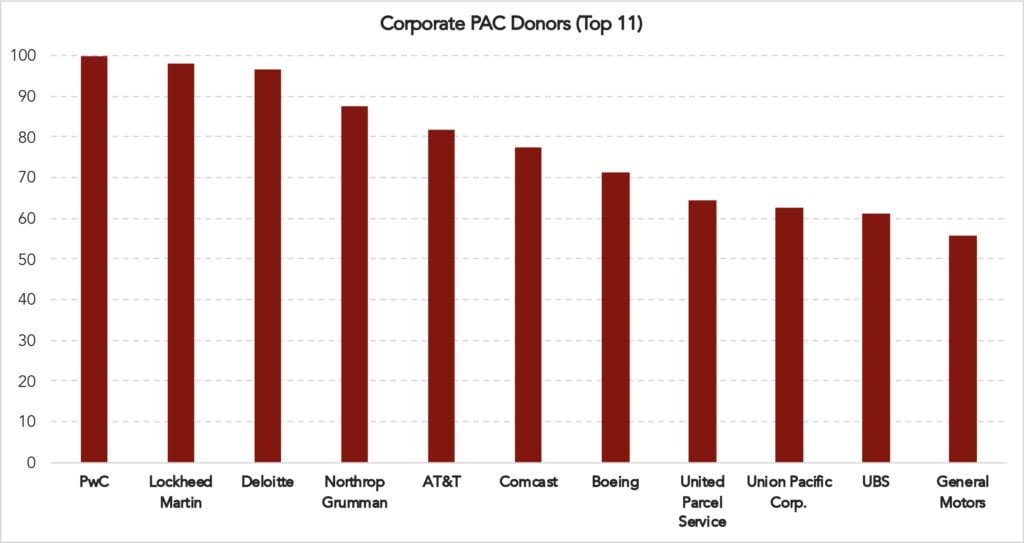

How did the actions of companies to pause, re-evaluate or halt giving via political action committees (PACs) to 147 or all U.S. House and Senate politicians play in the media? Data from Signal AI provided to Mark Weiner, PRNEWS columnist, Cognito executive and author of “PR Technology, Data and Insights,” sheds some light on this question.

Signal AI’s analysis focused on media coverage specifying the name of well-known companies on the topic of removing PAC funding. Of the 11 companies generating the highest scores, each organization’s total is on an article-level analysis. The scoring also includes sentiment toward the company, salience of the company in the news item and readership of the publication. 0 equals absolutely negative, 50 represents absolutely neutral and 100 is absolutely positive.

PWC, Lockheed and Deloitte lead the pack (pun not intended).

Some companies that chose to ‘consider an appropriate response’ or not to respond fell victim to criticism from journalists and social media.

Confirmation of the presidential election generated considerable interest outside of the US, as 60 of media coverage originated through domestic sources while 10.5 percent came from Europe. News from the US and Europe focused on companies that acted by withholding PAC funds to election-deniers: 99 percent of European coverage and 82.5 percent of US coverage commended companies that responded confidently, stated a position and then took decisive action on that position.

For Weiner, the data indicate “silence and equivocation speak loudly to Americans, who expect their employers, brands and investments to reflect their personal public values.” In this case, intrepid companies that acted, were rewarded for it.

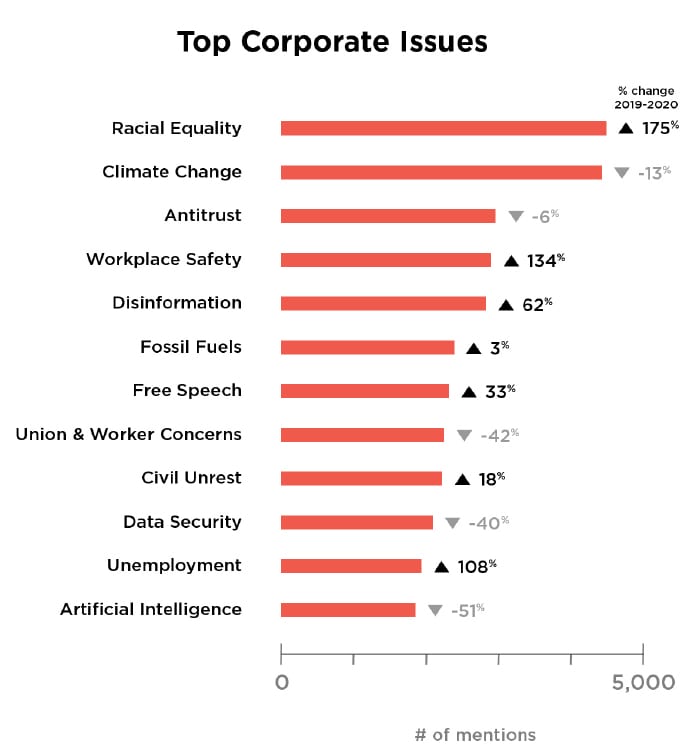

Major Issues for Reputation

Communicators will face melding corporate political giving with brand reputation in 2021. Certainly, the events of 2020 tee up other issues that communicators must address. Which ones? Data offers potential answers. Released late last month, High Lantern Group’s 3rd annual Brand Pressure Index analyzed 6 million 2020 tweets from 3,500 activists, influencers and political figures about 350 social issues and their intersection with 1,000 brands. Ranking is by number of mentions.

Mixed news as Black History Month begins: Racial Equality was the top issue, up a huge 175% vs the same period in 2019, yet Diversity & Inclusion is number 20 on the chart (not shown), down 18% since 2019.