The ubiquity of cybercrime has made communication about it a subspecialty that PR pros need to acquire. Or they must hire communicators and lawyers with knowledge of cyber jargon, technology, rules and regulations.

In general, PR pros are urged to communicate about cybercrime using the basics of crisis communication. Disclose facts clearly, promptly, authentically and transparently. Apologize genuinely to victims as you acknowledge the situation’s severity. And communicate procedures you’re instituting to prevent future crises.

Yet there are differences between communicating about cyberattacks and garden-variety PR crises. First, the communicator must walk a fine line on transparency. It’s often unclear in the early stages how much damage a hacker’s done. Of course, consumers want to know if their data was compromised. Sometimes it’s just not clear.

There’s another transparency issue. While the communicator needs to disclose information of an attack or breach to the public, she needs to determine what and how much information. Offering certain details could aid the hackers and/or potential hackers.

In addition, there is a plethora of federal and sometimes state rules and regulations for communicators to consider.

All that is difficult enough. Yet this summer one federal agency added to PR pros’ headache, acting for the first time against public companies’ communication of cybercrime.

SEC’s Focus on Communication

In several recent cases, the Security Exchange Commission (SEC) levied hefty fines and/or settled disputes for substantial dollar amounts with companies that, in its view, failed to communicate clearly and authentically about cyberattacks.

This is significant in that the SEC signaled for the first time that it considers cybercrime a business threat, akin to natural disasters, political and economic events and competitive issues, among others. The SEC requires public companies to clearly communicate threats to investors.

Kristin Miller, director of global communication at software firm Ping Identity, says the SEC’s recent actions elevate authentic and transparent communication beyond the realm of PR and reputation.

“Now there are legal reasons” to communicate accurately and promptly about cyber incidents, she says.

Adds attorney Stephen Riddick in the Harvard Business Review, “These fines signal a major shift, and one that could profoundly change the way companies think about cybersecurity threats, communicate internally about these threats, and disclose breaches.”

And while two of the companies in these examples acted well outside the lines of proper communication, one, First American Financial Corporation, thought it was acting properly, but was not. Equally important for PRNEWS readers is the fact that the SEC based its actions on how the firms communicated about cyber events.

The Three Actions

In the most recent action, announced Aug. 30, 2021, the SEC said the Cetera Financial Group of El Segundo, CA, sent notifications of data breaches to clients that included “misleading language.”

The issue, the SEC said, was that Cetera’s communication claimed it issued the notifications “much sooner” after the breach than was true. In other words, Cetera alleged it promptly informed customers of the breach. In the SEC’s opinion that wasn’t true.

The settlement was $300,000. In the incident, personal information of 4,400 customers and clients of the Cetera units was exposed between November 2017 and June 2020.

A Data Breach: Real or Theoretical?

Two weeks before that, on Aug. 16, the SEC settled a dispute with Pearson PLC, an educational publisher based in the UK, for $1 million. The data breach involved “theft of student data and administrator log-in credentials of 13,000 school, district and university customer accounts,” the SEC said.

In some of its communication, Pearson said the breach didn’t happen. For instance, in several 2019 communications, Pearson described the breach as “a possibility,” though it occurred in 2018.

In a case of corporate chutzpah run amok, Pearson’s 2019 semi-annual report, filed in July that year, said the breach was “a hypothetical risk,” the SEC said in a statement.

In addition, Pearson doubled down on what seems to be less-than-transparent communication. In a July 2019 statement to media, it said the breach “may include” dates of births and email addresses. In fact, the SEC said, “it knew that such records were stolen,” the SEC added.

On top of that, the company claimed it installed “strict protections” against future cyberattacks. “In fact, it failed to patch the critical vulnerability for six months after it was notified,” the SEC said.

Omits Pertinent Information

But wait, there’s more. Pearson’s above-mentioned media statement failed to include that “millions of rows of student data and usernames and hashed passwords were stolen.”

In addition, the SEC said Pearson’s internal communication was flawed. Procedures “were not designed to ensure that those responsible for making disclosure determinations” were properly briefed about the breach.

Adding a cherry on top, the SEC’s chief of cyber enforcement, Kristina Littman, said Pearson didn’t notify investors of the breach until the media contacted the company. “…and even then, Pearson understated the nature and scope of the incident, and overstated the company’s data protections.”

Pearson did not confirm or deny the SEC’s allegations.

Reporting Stymies Communication

A third case involves external and internal communication and illustrates the importance of disclosure procedures. Without such procedures, a breach can remain a secret, blocking prompt communication and other problems, as you’ll see in this next example.

The company cited in this situation, First American Financial Corporation, seemed to follow procedure and still was torched. It settled with the SEC for $500,000.

Immediately after a journalist informed First American of a breach that may have exposed some 800 million images dating back to 2003, including those containing customers’ social security numbers and financial information, the company issued a press statement. It filed forms disclosing the breach four days later with the SEC.

Yet the SEC found senior executives quoted in the release and the forms lacked enough information about the situation to render an accurate assessment.

First American, the SEC said, lacked adequate disclosure procedures. Such procedures should have ensured that information about the breach was sent up the chain of command when company employees found it initially.

Without such procedures, “senior management was completely unaware” of the company’s earlier discovery of the breach and its failure to correct it, the SEC’s Littman said.

Symbiotic Relationships

This last example highlights how cyber staff and communicators have a symbiotic relationship, says Bob Pearson, CEO of The Bliss Group and a PRNEWS Hall of Fame member. Just as poor communication can undermine an effective cybersecurity effort, this example shows how cyber procedures can delay critical communication.

“Cyber and communication experts need to work together” on procedures and policies so cybercrime “can be treated with the same high level of candor and attention,” that other issues receive, he adds.

Miller of Ping Identity emphasizes the need for legal to join communicators and cyber personnel in this work. When sensitive information is exposed, lawsuits tend to follow. In addition, the SEC penalties in the above cases were relatively light.

Recall the $35 million fine Yahoo! purchaser Altaba ponied to the SEC in 2018 to settle an action over Yahoo!’s failure to disclose a 2014 breach.

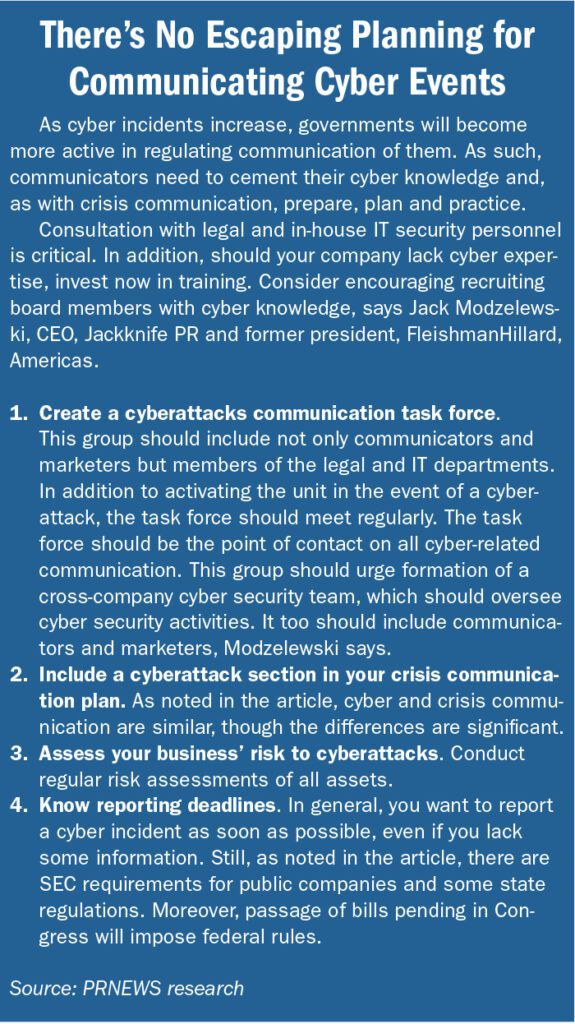

And as if the SEC’s regulation of public companies’ communication wasn’t enough, the volume of rules seems poised to grow. New proposals in Congress are pending that, if approved, will set time limits for when companies must report cyberattacks and ransomware payments.

At present, there is no federal law requiring companies, private and public, to report breaches to Washington.

In one bill, companies will have 24 hours to report ransomware payments and 72 hours to notify federal authorities of a cybersecurity incidents.

A proposal from Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) mandates companies report a cyber incident within 24 hours. Another proposal, from Sens. Rob Portman (R-OH) and Gary Peters (D-MI), specifies reporting times for firms in national security.

However, House-approved legislation prohibits reporting times of fewer than 72 hours. The House bill and Senate proposals have companies reporting to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

Pearson (no relation to above-cited Pearson PLC) cautions against concentrating on complexities.

“It’s important that communicators stick to the basics of issues management. Provide the truth with perspective, and do it promptly, to reflect how we’re protecting our company and its customers.”